Irrelevant. Unnecessary. Redundant. Delete. If you’re a writer and you’ve asked someone to review your work, you may have heard these words or seen them scribbled beside selected sentences and paragraphs of your draft. No matter how tactfully they are communicated, these kinds of comments can still feel like a slap in the face—especially if they are directed at work that you’ve labored on for hours.

Understandably, it’s easy to become defensive. “What!? You want me to scrap that entire paragraph? Don’t you appreciate how beautifully crafted those sentences are? Do you know how long it took me to write this?” Even if most of us are too polite to actually say these words out loud, more than a few of us have silently uttered them inside our heads as we feign a smile and thank our reviewers for their help.

Very often, though, it is necessary to face the harsh reality that some of our hard work simply needs to be deleted. Although it might be the last thing we want to do, it is sometimes our best course of action. This is especially true when writing applications for grants, fellowships, and other awards, which regularly have strict requirements regarding page limit or word count. Deleting extraneous information can free up room for writing about things that are more relevant to the application.

But the process of deleting one’s work isn’t easy. In fact, it can be downright painful. It can feel like a blow to your ego (“I was wrong to think this was important”). It can also feel like you were wasting your time (“Well there goes 3 hours of my life that I can never regain!”). In actuality, though, there’s very little reason to feel shame or remorse when deleting work.

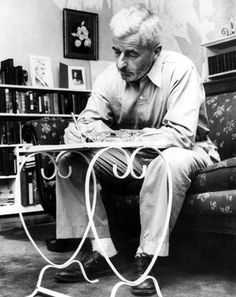

The best and most experienced writers agree that deleting portions of your work is not only part of the writing process—it is integral to it! The great American author and Nobel Prize winner William Faulkner put it most succinctly when he said “In writing, you must kill your darlings.” No matter how wonderfully written, evocative, or insightful a section is, you must be prepared to cut it from the final draft if it doesn’t meaningfully contribute to the overarching goal of your work.

Remember that when applying for an award, your main priority must always be the evaluation criteria of the funder. You must always be open and willing to adapt your application towards this goal. Everything else is secondary. It doesn’t matter how much time you spent on a section, or how eloquent it reads. If it does not augment your chances of winning the award, it should not be in the application.

Although “killing your darlings” is often necessary, there is no doubt that it can be a difficult process. Here are a few pointers to help make the murderous task a little easier:

- Seek out a trusted reviewer to comment on your work: If someone counsels you to kill your darlings, it is imperative that you trust his or her advice. This is why, when looking for someone to review a draft of your application, you ask only those people who are willing to put the time and energy into reading it thoroughly. Your faculty advisor is one possible source, as are the other members of your committee. Of course, one of the best sources of advice is GradFund, whose team of fellowship advisors and peer mentors are trained to read your work with the singular goal of making it more competitive.

- Save your deletions: When revising your application you can apply the strikethrough tool to delete portions of the text. If you cut out entire sections of your work, you can also save them in another document titled something like “Cuts,” “Deleted bits,” or “Darlings.” This is always a good idea, because some of what you erase from your current application may still be useful for future work.

- Be proud of your decision: Instead of interpreting your deleting as a blow to your ego, consider it a source of pride. You’ve overcome your attachment to superfluous writing that doesn’t advance your primary goal. You now have a better chance of winning an award! And in that sense, any time you “wasted” writing and then deleting parts of your application may now translate into time saved not applying for the same award next year.

- You are in good company: Regardless of the outcome of your current application, you have now adopted the same attitude and writing technique touted by many of the greatest writers. It’s bound to pay off in the long run.

Leave a Reply