So… you’ve visited GradFund with those shiny new application essays. We gave you a ton of feedback that you maybe weren’t quite expecting. You have to find a way to squeeze all of that into some arbitrary spaced laid out by a funder who just doesn’t seem to appreciate the fact that you have mountains of data and narrative that need to be represented. I mean, come on! Two pages? How’s that even possible? And then, seemingly out of nowhere, your friendly GradFund fellowship advisor suggests you also seek feedback from your advisor and other trusted faculty members… How can you squeeze even more feedback into this already overloaded space? Well, as you’ve probably heard us mention once or twice, faculty feedback is essential in constructing compelling research narratives. You and your advisor understand your disciplinary space far more completely than any of us. We consider ourselves experts in narrative construction, but you have to provide us with enough material to play with. Your advisor helps you do that.

Okay… So you get why we’re always talking about your advisor. Every. Single. Meeting. So you go ask her for advice. And she takes what looks like a red paintbrush to your proposal. Believe me, I’ve been there. Well, there’s a chance that a lot of her suggestions align with ours. That’s probably a good sign, right? We think so. But there may be one or two things that conflict with our advice. So what do you do?

You first need to consider that there isn’t only one perfect way to write a proposal. Different strategies in content and presentation can be equally viable if properly considered and implemented. Above all, however, written communication, especially narratives, should flow naturally. This isn’t an M. Night Shyamalan movie. There shouldn’t be a surprise twist ending. As a reviewer, I should know from the outset where you are going – because you hopefully told me where I was going. So it follows that you should choose the most natural path to get me there.

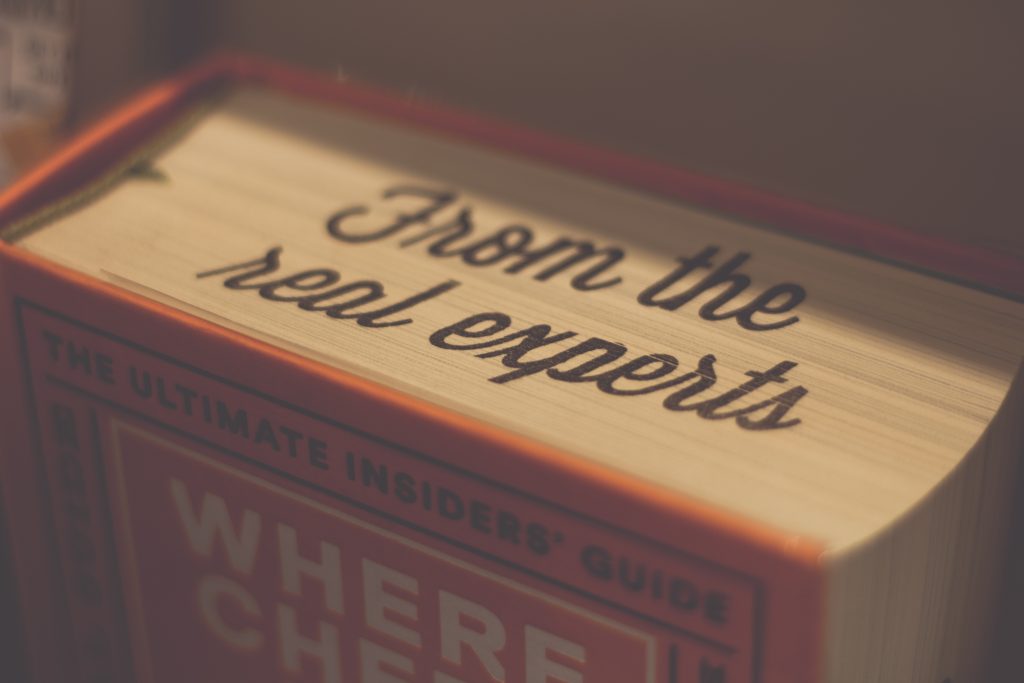

Your second consideration should be expertise. It’s entirely possible that your advisor may have a unique expertise in the award to which you are applying. Maybe they served as a reviewer. Maybe they served as a committee chair. Maybe they are a past winner. Maybe they are just as adept at narrative construction as we are. If any of these things are true, we do hope that you’ll let us know so that we can work in concert with their experience (through you, of course!) to help you optimize your competitiveness. Basically, you should take their experience into account as a way to contextualize their feedback.

Any and all of this advice applies to other sources of feedback as well. Maybe you ask your parents or siblings to read your work and offer feedback. Maybe you have other trusted advisors in addition to your primary PI. And, since our services don’t include proofreading for grammar or usage, maybe you ask a trusted colleague in your program to proofread your essays. However, there is one additional caveat to all of this. You should probably let your PI know that you are soliciting external feedback and from whom. They may also suggest some alternative sources of feedback that you haven’t considered. In this context, there really isn’t anything wrong with knowing a guy who knows a guy who has a cousin who used to head the NSF. We should all be so lucky.

These applications are your work, thus you should evaluate the advice separately and decide which one best fits into your narrative. You must consider the source of the advice and how their expertise contextualizes the advice. It boils down to a decision that, ultimately, only you can make.

Leave a Reply